The boom in the specialty coffee industry has been on for several years. Baristas are tirelessly gaining experience, broadening their knowledge of coffee, honing their skills, and mastering modern techniques. Over time, their profession has become more and more interdisciplinary. However, my impression is that the increase of professionalism is missing one of the basic coffee-related areas. It seems to me that baristas know more about botanical varieties, terroir or processing methods than they do about roasting coffee. This is no surprise – a lot of reliable, basic information about what is happening on the plantations is available online. Whereas roasting is still largely treated like a secret knowledge, a craft for the chosen ones. So, what is coffee roasting and how does it look like? Let’s find out!

Why so secret?

Lighter roasting of high-quality Arabica in craft roasteries is a new and, therefore, still underdeveloped area. Everything was trivial as long as all coffee was roasted dark, and, consequently, every brew tasted very similar.

The famous third wave of coffee forced the roasters (i.e. people who roast coffee, editor’s note) to significantly expand their knowledge, develop analytical and sensory skills, and gain a lot of patience and humility. Hundreds of theories are analyzed every day on geek forums for roasters. Among them: truths, half-truths, understatements, myths and incorrect assumptions. One person says one thing, the other says otherwise. The third one overthrows both foundations, and the fourth one counters all three, convinced that he is right. Some roasters cooperate with each other and share even the smallest variables, others treat their conclusions and profiles like little Amber Rooms. Knowledge is largely passed on in closed master-student relationships. Otherwise, it is gained from several published books, none of which has so far been a decent and comprehensive compendium of knowledge from A to Z.

Finally, the techniques and styles of roasting coffee that provide the desired results are relatively numerous. Let’s add local preferences to that. Roast from Solberg & Hansen or Johan & Nystrom can be considered undeveloped and sour in the United States. And in Goteborg they will say that Melbourne coffee is definitely too dark and bitter…

Let’s put it all aside for a moment. It would be nice if the basic information on coffee roasting was available to as many people as possible. I will try to present some of the foundations of roasting in a simple form and, I believe, paint an elementary picture of what it is all about.

Roaster

Coffee is roasted in specialized roasters. Shocking! The vast majority of them are the so-called drum roasters. They are usually powered by fuel in the form of flammable gas. The most important element of such a machine is:

Drum

It’s a bit like in a washing machine. It’s cylindrical and it spins. Inside the drum there are paddles, which scoop the beans to ensure them an even, cyclical, rotational journey through the roasting process.

Flame

It is located directly under the drum. It turns the fuel supplied to it into a flame, the intensity of which is controlled by the operator. The flame is a source of energy – it heats the drum to the desired temperatures, which roasts the coffee.

Cooling tray

Placed directly under the exit, through which the roasted coffee is dropped at the right moment, thus completing the roast. It’s necessary to cool the beans in order to stop the chemical reactions that have just taken place in them as quickly as possible. Therefore, just before the drop, the operator starts the mixer and a separate engine which draws in the air from the environment, cooling the heated material. The mixer arms, similar to the blades within the drum, ensure even distribution of the coffee beans during the roasting process.

Chimney

A simple thing – hot air roasts the coffee, it goes through the drum and has to get away somewhere. Part of the dust and suspended particles from the raw material and the smoke generated in the final stage of roasting also get away with it. So does the air, transported through a separate channel, which cools the beans.

Panel

For clicking, starting, changing and switching. It’s the roasting command center, captain’s bridge.

The roasting process

Coffee is a strikingly complex raw material. It is estimated that there are over 1,000 chemical compounds in roasted Arabica beans. Over 700 of them are odorants, i.e. substances responsible for the aroma impression. Even relatively small changes in the pool of substances contained in the beans will bring out completely different characteristics in the ground coffee, not to mention the brew. This is a chemical explanation for why we can easily sense the differences between the Kenyan SL 28 and the Peruvian caturra.

Strecker, trigonelline, sugars, acids, amino acids and lipids degradations, caramelization, Maillard reactions… This is just a small share of the most important processes taking place in roasted coffee, the complexity of which is a major headache for many chemists. Two of them have actually told me that. This is not the place and time to delve into the detailed depths of these phenomena, but here’s some interesting trivia.

Sensing specific aromas in coffee is not just fancy hipsterism. Here are some popular aromas in the specialty-quality Arabica and the chemical compounds behind them, formed during the syntheses:

- nuts and their roasting aromas: thiophenes, oxazoles, pyrazine, thiazole

- bitterness: pyridine, phenols, furans

- caramel, honey: thiophenes

- fruitiness: many compounds with a carbonyl group (e.g. aldehydes), acids, sugars

One more argument for the defenders of the perpetual cause of “arabika>robusta”:

Arabica contains about 60% more lipids than robusta. Many odorants are lipid soluble – it’s important for the perception of aromas. Robusta simply has less “lift” for the odors.

34 acids have been identified in roasted coffee. Most of them are volatile substances that contribute to the perception of aroma. This is one of the reasons why coffee is aging. The longer you store your beans, the more volatile substances “escape” from them.

The longer the coffee is roasted, the more:

- acidity decreases

- bitterness increases

- sweetness rises and then diminishes

- body increases and then decreases

The famous crack

The so-called crack is a very important moment for a roaster. Anyone who has ever successfully made popcorn in a microwave or a special machine (the principle of which is alike to an oven) has made it happen, only with corn. At some point, the water in the roasted coffee beans turns into steam. Increasing pressure builds up. As the fruit grows in size, it begins to crack and steam escapes. This moment is marked by specific noises that can be compared to the loud destruction of air bubbles from the bubble foil.

The energy and time of entering into the crack, as well as the course of the roast from this point to the drop – this is what (in aspect of roasting) will have the most important influence on the taste of the brew. It is mainly this stage that determines whether your Kenya on the cupping table is full, clean and sweet.

Roasting profile

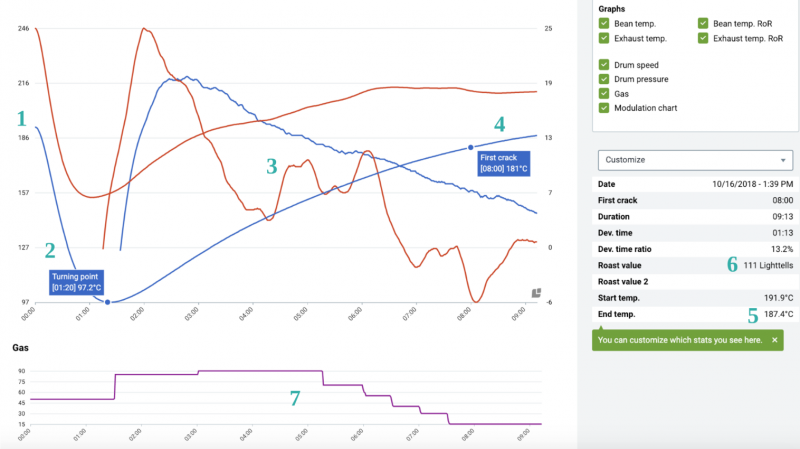

Here is a typical roasting profile graph from a popular software designed for professional roasters.

The two blue lines represent what is happening to the bean. These are two sides of the same coin. Classic yin and yang. A descending line followed by an increasing line is the reading of the raw material temperature change over time. The rising and then falling line represents the so-called Rate of Rise – the rate at which temperature increases over time. You can see that at the very beginning the value increases and climbs up to a certain point, then declines in time until the drop. This does not mean, however, that the temperature is starting to drop. Only its rise is smaller. The use of RoR and the way it is applied is key in modern coffee roasting.

To put it very simply: RoR is an indicator of the “speed” of chemical reactions in the bean. Hence its enormous importance. A RoR that is too low may cause some key flavor reactions to be too slow or even absent. Characteristic notes in a cup: papery taste, roughness, lack of sweetness, unbalanced acidity. The application of too high a temperature rise can result in too much difference between the center of the bean, which will remain to some extent raw, and its outer surface. The roasted coffee will not develop properly. Notes: “green” flavors and aromas (peas, grass, asparagus), at the same time a smoky, bitter sensation. No sweetness.

The red, analogous graphs represent the air temperature in the machine. They are largely related to the blue charts, but they are governed by slightly different rules. Here is the rest from the picture:

Roast start and drop temperature reading. A notorious lie! In fact, the temperature of the bean rises almost immediately. This is simply the reaction of the probe, stunned by the sudden drop in temperature caused by a charge at room temperature being dropped into the hot furnace. The moment that starts the rise of the curve is called the “turning point”. From now on, we are much closer to the truth.

The middle stage of the roast. The bean is already very dry, it has gained a lot of energy. Important chemical reactions are about to begin. This is also a good time to direct the correct entry into the crack. In many ways, the most important moment of the roast is the stage from crack to drop. This is the moment of selecting the right energy that will guarantee the proper development of the coffee.

Drop temperature, that is the end of the roast. The degree of the roast, or the color of the bean after roasting. While the RoR determines the speed of the reaction, the color determines the degree of the roast. It is measured with special tools called colorimeters.

Finally, there’s a graph of burner power management over time, expressed as a percentage.

Roasting coffee at home – will it work?

Roaster’s work is a complex and nuanced activity. Is roasting coffee at home without specialized equipment and complicated measurements likely to be successful? Theoretically, yes. I’ve already mentioned that the process of roasting coffee is like making popcorn at home. For obvious reasons, coffee roasted without precise control over the parameters mentioned above will differ from the coffee professional roasteries offer. So, it’s better to try with less expensive beans, at least at the beginning, and then decide if the game is worth playing. So, how to roast coffee at home?

You need an oven or a pan or a popcorn maker for this. If you use an oven, it must first be heated to the highest possible temperature (usually 280 degrees Celsius). Coffee beans should be evenly distributed on the baking tray and then put into the hot oven. When roasting coffee at home, we cannot control indicators such as RoR or changes in coffee temperature. So, we do not leave the oven and wait for the first crack. Similar to roasting in a roasting machine, what happens next depends on our trials and experiments. However, you must remember that immediately after taking it out of the oven, the coffee should be cooled down, e.g. by pouring it from one container to another or tossing it on a sieve.

If you choose to roast coffee in a pan, the rules are similar. The coffee gets to a dry, hot pan, but throughout the process you need to stir the beans so that they roast evenly. You wait for the crack, then observe the color of the beans, and then remove them from the pan and cool them down. If you have a popcorn machine, you don’t have to worry about mixing the beans.

And that would be all about the basics, or rather the basics of the basics of coffee roasting. Cheerio!